We Saw a Nest

| by Pear Nuallak |

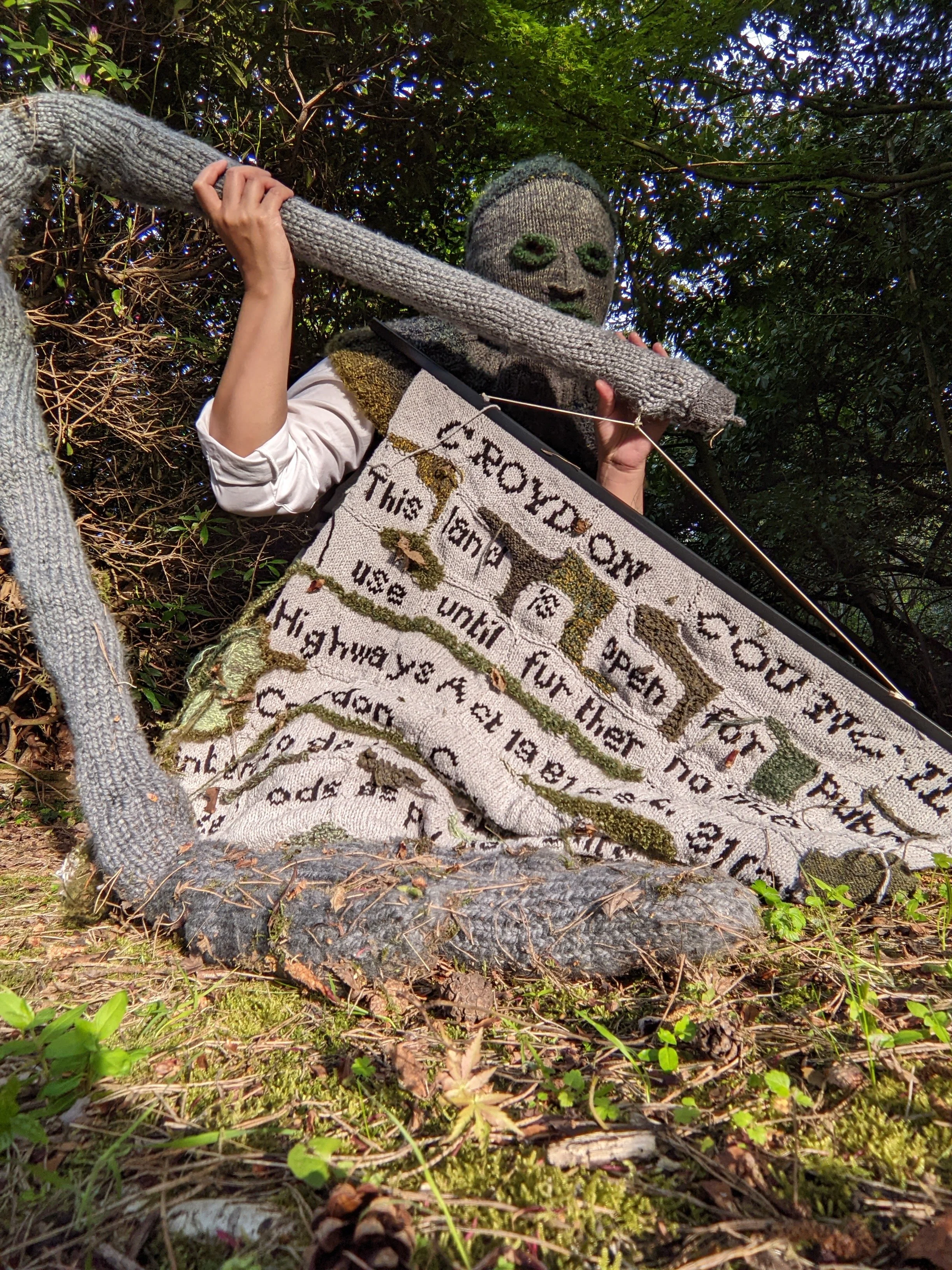

Golden light with shadowy background foliage frame the author sitting on the ground wearing a knitted grey and mossy mask holding a crumpled knitted grey and mossy street sign.

Watching Tongpan (1977) with my parents at the ICA, I consider our shared history. Created by the Isan Film Group after a student-led mass uprising against dictatorship, Tongpan shows capitalists from Bangkok and America dispossessing Isan of its own people. We see Isan farmers bravely struggling until they, too, are transformed into diverted resources. Purposefully impoverished, Isan people often face the constrained choice to stay and fight or become a workforce bound for Bangkok, the rest of Asia, and the West.

Tongpan is the story of my family, among many others. Our reality dispersed, again and again.

Yellow hand pointing to a medieval pisswheel with PISS IN THE SAME POT in gothic blackletter written around the circumference. Dyed textile samples inside round urine bottles gradate from pink to blue.

2.

Climbing to the intelligentsia from domestic work and food service meant a favourable UK visa for my parents. Once artists, they secluded themselves in the hills by the Surrey-Kent border as live-in housekeepers to a white English retiree who specifically desired Thai servitude. “We saw a nest,” my parents later said of their move. My child-self accepted this for the sake of an English education (mediocre state schools). We adored the garden, growing into Englishness among the rhododendrons, oaks and roses.

In my 30s, I relearn my anger and my childhood land as a commons with burial mounds and a brook dedicated to Thor. Histories of ownership frustrate me around posh houses and golf courses, before I can breathe in public green space where mining bees wriggle home underground. I find two long-tailed tit nests, woven moss and cobweb. (I don’t touch them.)

A collage featuring a hand holding green oakmoss fronds against a background gradient of brown-to-burgundy dye, surrounded by twists of fine wool in soft mauves and pinks.

3.

I think of historical textile workers and their deep knowledge, strong stomachs and self- implication in environmental extraction as I gather a small handful of abundant windfall oakmoss from the commons — intending to digest this into dye with urine. Time, oxygen and alkalinity make pink wool samples with an alleyway stench that diminishes into rich mossy fragrance. The symbiotic relationship we know as lichen has human and nonhuman use: nest, food, perfume, dye. My childhood makes more sense after this research.

Although I still don’t know anyone else who grew up quite like us, our story is not a singular tragedy. Workers in much harder conditions fight back, such as the women of the Filipino Domestic Workers Association. My own work is not direct resistance. My walking, research and making are small personal rituals that aid my digestion of being simultaneously victimised by and implicated in racial capitalism. It supports my critical attention to what’s disgusting, discarded, invisiblised. With stained hands, I stitch the gap in diasporic experience with humility, offering knowledge as compost.